Let me say a few words on the Culture of the Amateurs in the Museum. Correction. Let me better say a few words on the Culture of the Makers in the Museum (and its history).

Making is a cognitive and motoric process. It is seen as an act of forming, causing, or constituting, and as a process of growth or development. The cultures of DIY/DIWO/DITO (do-it-yourself, do-it-with-others, do-it-together) approaches are an integral part of all world wide cultures for hundreds of thousands of years. Civilizations were built on the strengths of the DIY communities, it is just about how the term was used and sometimes misused in the mainstream. These are in essence all the arts and crafts based activities. They were oriented towards the improvement and/or innovation in life. Artisans laid the foundations of craftsmanship in every culture.

So why then are we putting the DIY culture in the box of amateurism sometimes?

The marvelous stories of citizen science began to spread in the public thanks to the many individuals who were creating and collecting scientific manuscripts or data for centuries. Through giving their part to the huge framework of all sorts of sciences from natural to social all the way to the formal science nowadays. Of course, in their time, there was also a limited access to these pools of knowledge. But then they found their life in museums, localities, archeological sites and libraries we call nowadays cultural industries. Today they are all integral part of the cultural history of science. Most of the time they were part of the educated elite, but bottom-up and grassroots approaches and movements were also making its own ways to the society and its audiences building along their very own way to the communities too.

The tendencies towards innovation were present in the form of survivalism, but also with an aim of simplifying complex problems. It is considered that a DIY term is present in the Western civilisation of the modern age in everyday use since the post-war crisis. That is during the impoverished 1950s when objects were not simply discarded, but repaired, and used for a lifetime. Therefore, we can say that WE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN MAKERS. I am paraphrasing here the poster by Hackteria – a Network for Open Source Biological Art that states We Have Always Been Biohackers.

Parallel to these processes, the Arts and Humanities also embraced the culture of DIY and making for diverse reasons – economical (being poor or of lower income), social (being excluded), technical (again, being poor) or as an act of statement. If we look at the Fluxus movement, we see a lot of DIY artistic methods, then checking for instance at the Punk movement, all about ‘dirty’ DIY exposed to the bones, or the garage science (always shyly present in its fog of anonymity but never acknowledged enough). But all of these examples had activities with a lot of “getting your hands dirty” methodology.

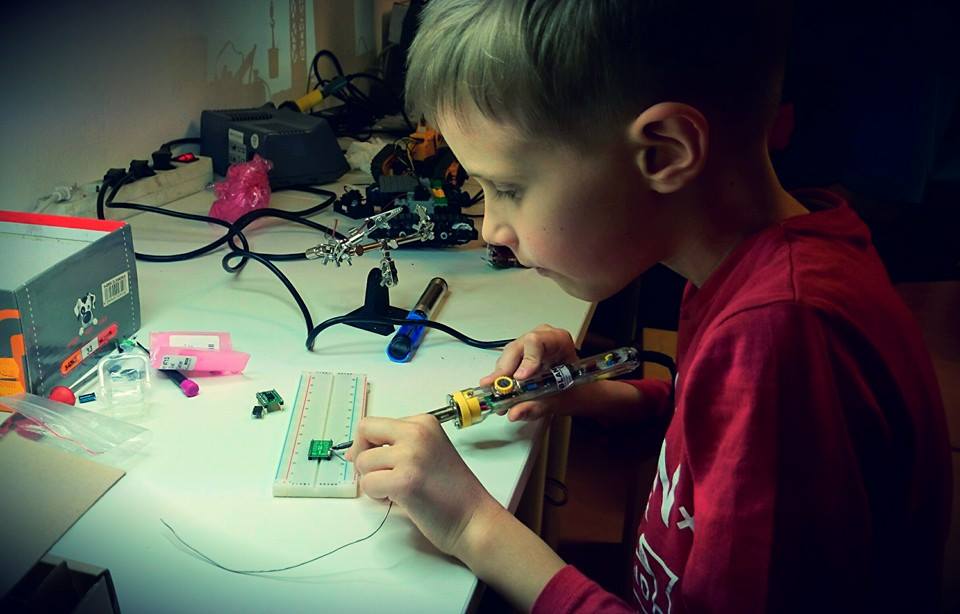

Photo: We Have Always Been Makers, Radiona (CC BY 4.0)

Then we teleport ourselves into the 2000s and we see the rise of the maker culture. We see makerspaces, hackerspaces, media labs, fablabs, repair cafés, libraries of tools, creative spaces all driven by high tech and low tech. We see soldering, programming, people creating circuits or crazy robots, interactive installations with living systems, parallel virtual worlds, you name it. We started to read or listen about Arduino, Raspberry Pi, Teensy, sensors, IoT and smart cities, and lately about AI and machine learning. We started visiting Maker Fairs and all sorts of innovation based fairs, new media festivals and hackathons. All of these occurrences are/were also shaping our formal and non-formal education across the globe and they started to shape our lives too.

The question we have to answer as humanity is the following: are we all using technology for ourselves, or the technology is using us?, as Douglas Rushkoff would problematize it in his book Program or be Programmed: Ten Commands for a Digital Age (2010). Seems like in the process of finding the answers we will need a lot of social sciences, as well as motoric and cognitive processes.

Why DIY Cultures Shouldn’t Be Perceived Anymore As Subcultures

If we look again into the social science we see that the French anthropologist Claude Levi Strauss in his book The Savage Mind (1962) has used the term bricolage in order to describe the difference between the French handyman (Monsieur Bricolage) as someone who uses a non specialized tools for a wide variety of purposes dealing with obstacles, pre-constraints or any kind of limits, whilst an engineer is using his specialized tools. As Claude Lévi Strauss concluded, bricolage is describing the specific patterns of mythological thought in the culture. Hence, bricolage is opposed to the engineer's creative thinking, which proceeds from goals to means, whilst mythical thought attempts to reuse available materials in order to solve new problems.

As you can see the solution making and tinkering is part of every culture, no matter if it is a high tech or a low tech based society. We can see that the maker cultures are actually interlaced with creativity and cultural histories, but they are changing with time and surroundings.

Makerspaces are sometimes perceived as a hobby approach in comparison with the serious professional approach, which makes for no reason the culture of makers being understated. Maker/hacker cultures and hybrid arts are actually eclectic practices on the wider spectrum of culture and education.

If we look at the possible collaborative practices between makerspaces and museums, we have to understand how both sectors are functioning from the policy point of view and organisational structure.

Makerspaces are bottom-up based self organised communities and organisations having in the centre people, tools and skills, whilst museums are top-down based institutions as public, private or hybrid legal bodies with collections, staff and facilities having as their core. What is called community in the makerspaces could be seen as actually audience development for museums, but in the last few years there is a strong tendency in the museum sector to transform the audience into community, and vice versa. Makerspaces, depending on their structure, can also develop and work on its audiences. There are examples of makerspaces being based at the universities, innovation centres and museums (museum labs), making them a part of the institutional framework.

Photo: Exhibition Fly Me To The Moon (2017) by Radiona.org, Technical Museum Nikola Tesla (CC by 4.0)

When starting a collaboration between the makerspace and museum, it is of highest importance to know very well the policies of the museum and how it functions: the roles, closing hours, alarm system, fire protection, copyright issues, formalities, the basics how collections are protected and preserved in order to avoid possible misunderstandings.

Makerspaces are places for tinkering, prototyping, community building, peer-to-peer skill sharing and exchange, open source approaches (opposite to copyright) and usually identified as free and a non-formal places.

Both sides have similarities and differences when developing access to means and participation. The topics that should be always discussed and clarified are about the boundaries and lines that could be crossed in the creative process during their cooperation.

When talking about the makerspaces, we have to mention hackerspaces as the foundations and as “historical” preceders where makerspaces were born, if we perceive it in a very romantic way. Hackerspaces are community-operated, usually "not for profit", as a workspace where people of common interest in open source technology, programming, mechanics, science, engineering, and hybrid arts are socializing together.

Photo: Hoverboard by Igor Brkić & Damir Prizmić, Radiona.org (CC BY 4.0)

Hackerspaces are usually self-maintained with the community of people who do not want its practices to be a part of the formal system and it should be respected as such. It is an autonomous zone, as Hakim Bey would state.

One of the reasons why hackerspaces got a mainstream bad stigma is the fact that the media created this image of a hacker sitting in a dark room with a hoodie hacking credit cards or accounts in front of the screen that looks like a scene from the Matrix movie. This image is far from true. Programming in different interfaces does not look like a scene from an action or SF movie, it is far more boring looking at the black or white screen trying to find a bug in the code.

Nowadays, there are so many hybrid variants of makerspaces, some having their DNA in hackerspaces, whilst some not being even aware of the existence of the whole universe consisting of experimental, creative or residential spaces for such practices.

Museum Labs

In my own experience of running Radiona – Zagreb Makerspace from 2010 from a bunk space that was all dirty (but mostly loved by the community and participants) to the space where the visitors “feel like home”, it is crucially to take into perspective realistic goals and visions that are achievable:

- For a makerspace or creative space within a museum, it is important to create a space where people are not afraid to get out of their comfort zones (sounds like a buzzword, but it was tested and proved through the practice over years).

- In order to diversify it from the library of tools it is good to have a diversity in the program of the makerspace, so community and audience can sometimes interlace creating an ecosystem that has a long term potential.

- Setting up the space where people cannot injure themselves should be first on the list of priorities, as it could cause a legal problem for each partner, not to mention the emotional stress and pain it brings to the facilitators and partners.

- Makerspace or a museum lab has a great potential for being an intergenerational playground and a generator of creative practices for future generations.

- Creating a space that is based on collaborative practices means that social cohesion and inclusion are the pillars of social practices being transferred through the space and its activities.

- Facilitation of diverse professions is sometimes necessary as they very often ‘do not speak the same language’ so to say, in order to avoid any kind of misunderstanding between different professions. In this way mutual understanding, social interactions and fruitful collaboration could succeed between the artist and technologists.

- The creative space/makerspace/museum lab should quarterly do the complete scan of the audiences and community having in mind participation practices that could be developed considering all nuances and perspectives.

- Fostering and supporting citizen science with its diverse practices through the examples of practices like the birdwatchers, Jane’s walk, urban gardening, time banking concepts, could be inspirational for the participants of the museum labs.

- It is necessary to understand that having only machines and tools in the spaces does not mean people will start to gather by themselves. Machines have to be maintained, so it is good for the museum to have a good connection with the local makerspace who can deliver some program and its community there, on this way encouraging the museum audience to try to tinker or learn how to use the machines like the 3D printer, laser cutter and similar.

- Sometimes the audience is not showing up or sustain themselves as a regular user of the museum lab, so it is good for the museum to do the workshops in local communities in the neighbourhood or distant parts of the city with an aim of reaching new audiences (not just having middle class, white audience), but also to include suburbia citizens.

Resilient communities – Makerspaces as cultural centers

Radiona – Zagreb Makerspace has faced a critical situation in 2013 when the lab was asked to leave the premises because of the change of the management of the institution where the lab was located and we were not part of their future vision.

It happened during the hottest summer months and the community reacted with the approach of using what we had at the time – the public space. We organised a series of Soldering picnics in the public parks and cafes bringing equipment and started to do the workshops. People who were walking their dogs would check what we are doing and join the workshops. This was a clear example of a guerilla approach (similar to guerilla marketing) of using public spaces and creating a resilient community. In a few weeks we were accepted as a residential lab in the local gallery for contemporary art struggling at that time with the audiences, and in a few months the organisation had won its first grant as a space for culture for renting the premises for the lab. Resilience is crucial not just in times of crisis, but in everyday functioning of the organisation running a makerspace.

Self-sustainable makerspaces

Self-sustainable makerspaces are more based on the organisational structures of hackerspaces being totally funded through membership fees. Some examples are the TOG Hackerspace in Dublin, Metalab in Vienna and the majority of hackerspaces and makerspaces in the USA because of different ways of public funding.

In our experience, we have found very interesting the example of Hackheim in Trondheim (Norway) where the local owner of the co-working space/brunch cafe is understanding the concept of hackerspace and gave the whole basement for the use to the local hackers and makers for their activities, asking them few times per year to build him some lucid and simple device the co-working space can use for promotion of their space.

Innovative entrepreneurial practices – Hacking the Covid-19 unintentionally

Radiona was working for the last two years on creating the ULX3S FPGA development board that is open source and is offering the best technical possibilities on the FPGA market. FPGA is a field-programmable gate array as an integrated circuit designed to be configured by a customer or a designer after manufacturing. It can simulate almost any machine and it is used in high-end technology projects.

The lab wanted to start the productions, but as a non-profit organisation we were aware that this could be a problem, so we launched the international crowdfunding campaign on the first day of the lockdown in Croatia (March, 2020). We did not have big expectations, especially as the campaign was launched on Saturday evening at 6pm. In an hour the campaign was funded 116%, in 25 days 750%. Nobody got super rich, but our peer in the lab – Goran got an opportunity to change his job and we established a company to maintain the ULX3S open source board that could be bought now in all relevant shops in the world. In this way the community got great feedback on their work, it created a new job opportunity and a legal body. Our peer Goran continues now to develop the company and offers jobs to the community members with diverse skills, like the 3D modelling for an artist who is searching for a new job or programming for a peer who recently got a baby and needs some additional work, and many more. In this way the lab is creating a vibrant, creative ecosystem and diverse community, although the entrepreneurial aspect is not crucial for it. It is just a consequence of working actions.

Heritage through the perspective of the makerspace

The benefit and affirmative approaches towards the museum collection in collaboration with the museum or a cultural institution are endless. As a lab, Radiona – Zagreb Makerspace is collaborating with the Technical Museum Nikola Tesla from 2013. We have a yearly program with an exhibition, a series of workshops and we brought to the museum Creative Museum international conference and Museomix hackathon.

Photo: Artefact leaving the museum - robot designed at Radiona.org (CC BY 4.0)

The exhibitions we did for the museum were from sound art, sonology and robotics to flying objects, gaming playgrounds towards science fiction and bio art. The best words that described our collaboration happened when we finished one exhibition and the robotic installation was recorded while leaving the museum. The staff of the museum published the video on its official Facebook page with a sentence: The future is happening now, the museum artefacts are leaving the museum on their own!

If we take into perspective specific areas of digital arts, it is obvious that many of the works created at the end of the 1990’s are already considered as a heritage. For us as a lab interested in sound art and building DIY synthesizers it is important to nurture the interest not only for repairing the old sound boxes, but also to anticipate research and promotion of the synth heritage. This resulted in many program lines regarding the obsolete but precious technologies which are now part of the museum collections, but also to reflect on the contemporary practices, like when our DIY synthesizer Synthomir was exhibited at the Venice Biennale of Architecture (2016).

This was the situation when the audience could see the importance of the maker culture, the same as the museums could see why makers should be actively involved in museum spaces.

Participation could be two directional.

People could feel more invited into “reading” collections from different perspectives with the help of makers.

Museums could also become experimental laboratories.

Audiences could become communities.

WE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN MAKERS.

Written by Deborah Hustic, Radiona – Zagreb Makerspace

Article republished from www.cremaproject.eu Since October, 2019 Think tank Creative Museum is part of the CREMA or CREative MAking for Lifelong Learning. CREMA is 3 year ERASMUS+ project (2019 – 2022).

Cover photo: Robotica Noir Workshop by Radiona (CC BY 4.0)