Kenneth Hudson, founder of the prestigious European Museum of the Year Award (EMYA), published his best-selling book Museums of Influence[1] in 1987.

In this work, he reviewed the development of the world's museums over the past 200 years by identifying 37 pioneers in ten countries, from iconic museums in major metropolises to small but innovative ones in remote corners of the planet. According to Hudson, amidst this diversity a small number can be singled out by way of pars pro toto. That is, viewing a single institution as a kind of normative model which has fundamentally influenced museum thinking and practice.

In the newly published (2021) Revisiting Museums of Influence. Four Decades of Innovation and Public Quality in European Museums[2], the European Museum Forum, a UK registered charity which runs the EMYA under the auspices of the Council of Europe, has reflected upon Hudson’s legacy and made a new selection of ”museums of influence.” Reviewing the nearly 1900 new or renovated museum applications to the scheme from 44 countries over 42 years, current and former EMYA jury members was asked to come up with a shortlist of institutions reflecting the qualities associated with museum of influence as defined by Hudson.

Assessing the initially proposed 200 museums, the editors of the book first applied criteria such as the type and geographical location of the museum, so as to cover the 47 member states of the Council of Europe. Additionally, the editorial board made sure that proposals came from judges representing different generations. However, the key criterion was that after many decades of working in, visiting and assessing museums, these were the ones the authors wished to write about.

At the Žanis Lipke Memorial, we were honoured to learn earlier this year that our institution is among the 50 museums included in the list. What was the justification before being selected as the only museum in the Baltic region? In 2014, the Žanis Lipke Memorial was awarded the Kenneth Hudson Award, a special prize created in 2010 as part of the EMYA project to carry forward the spirit of Hudson’s work, by recognizing a person, project or group of people who have demonstrated the most unusual, daring and, perhaps, controversial achievement which challenges the common perceptions of the role of museum in society[3].

So how exactly did the Žanis Lipke Memorial challenge perceptions? Firstly, this memorial museum dedicated to Žanis Lipke, Latvia’s most famous rescuer of people during the Second World War, located on Ķīpsala Island in Riga, was a private initiative created entirely through donations.

Secondly, according to the author of its scenario, Viktors Jansons, it should be viewed as “a work of art”, “a metaphor”, and “a pure idea”[4]. The EMYA judge who assessed the newly opened memorial back in 2014 and wrote an essay about the Žanis Lipke Memorial in the 2021 edition of Museums of Influence stated: “It could have been a novel, but it is a museum.”[5]

The formula can be summed up as ”a powerful confluence of remembrance and imagination”[6]. This was said about the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam, and it is a recurring reference when thinking about impactful communication by a memorial museum dealing with dark chapters in recent history.

The Žanis Lipke Memorial is still a young institution. In its 10th year of operation, it is just getting started with blending remembrance and imagination in order to reach broader international audiences.

In this presentation, I will look first at the Žanis Lipke Memorial in a broader European perspective of ”museums of influence”. Secondly, I view it in the context of Holocaust remembrance in Latvia.

The rich background of a successful, internationally acclaimed innovation in communicating the difficult past will serve as a reference prior to touching upon the institution’s future development plans.

Keeping in mind these two points of departure – a private initiative to commemorate the act of civil resistance in Nazi occupied Latvia, and the importance of imagination in doing that – I will reflect upon what makes interpretation and communication of the difficult past influential, even when done by a small memorial museum.

European Museum of the Year Award

In speaking about museums of influence, a short introduction about the philosophy and values of the EMYA is required.

As already mentioned, Kenneth Hudson’s original Museums of Influence appeared in the mid-1980s. This took place during a decade when the advance of neoliberal economics also compelled the public sector to modernize. And because museums are seen primarily as public services in the UK, the pressure for accountability was on as soon as Mrs. Thatcher was sworn into office in 1979. The traditionally ambivalent attitude in the UK towards funding culture, with the traditionally strong orientation towards the capitalist USA rather than social economic continental Europe, necessitated a remarkable change in museums. Following the British example, public quality and innovation became the mantra of museums in the last two decades of the 20th century.

Hudson gave a brilliant analysis of the state of the museums of his day against a broad historical background. Having named the types of museums in chronological order of their development – antiquarian and archaeologist, temple of art, nature and environment, science, technologies and production, national and local history – he then arrives at the newcomer to the family – the history in its place of action museum. These are archaeological sites in the broadest sense, i.e. houses, battlefields, or a shed in the yard in the case of the Žanis Lipke Memorial. The in situ parameter is crucial here. This type of museum is often located in proximity to the site of some dramatic historic event. Hudson mentions the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and Museum and the Anne Frank House as outstanding examples of this type of museum. However, his ultimate ”museum of influence” in this category is the Vasa Museum in Stockholm, a 17th century royal Swedish ship that has been salvaged with a complete set of objects on board. As one of Scandinavia's most visited museums[7], the Vasa Museum demonstrates the popularity of a phenomenon termed since the mid-1990s as the “dark tourism”[8], which is also present in regions which were largely spared by the horrors of 20th century totalitarianism. Similarly, the Anne Frank House in Amsterdam and the many Holocaust memorials further east are very popular among both locals and tourists, provided that they not only mark the site of a past dramatic event but also have a program. Programmed public work is what makes the difference at a memorial site.

This aspect of a museum’s work, i.e. public quality and raising standards across Europe, prompted Hudson to liaise with the Council of Europe to initiate the award scheme. On a deeper philosophical level, he was undoubtedly motivated by the value system on which the civilized world agreed after the Second World War, with its somewhat idealistical vision of a European Communities (the later European Union) as the materialization of a new vision for the continent. This value system is the foundation of bottom-up cultural heritage networking initiatives like Europa Nostra (1963) and the European Museum Forum (1977).

As a member of the Second World War generation, Hudson knew exactly what was at stake. As a down to earth realist, he didn’t position museums as problem solvers or agents of change as later generations of museologists would. But he clearly saw museums as a means to an end, not just repositories of stuff. His dictum that all museums have one major dilemma to deal with, which is how to make a visitor more self-confident, became the reference for the generations of judges and correspondents of the European Museum Forum who continued his work.

So, the program is the key. I will come back to this question in the context of a memorial museum, or by extension heritage industry, later when I discuss the case of the Žanis Lipke Memorial. But a quick look at the nominees of the Kenneth Hudson award may be helpful in comprehending what exactly is invested in the prize named after him.

Since 2010, the award has been given, among other, to the Museum of Contraception and Abortion in Vienna (2010), the Museum of Broken Relationships in Zagreb (2011), the Glasnevin Cemetery Museum in Dublin (2012), the Žanis Lipke Memorial (2014), and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum (2015). In short, museums that have a strong public profile and serve as a platform for discussing sensitive and at times controversial issues. Museums that do not hide behind the bushes when it comes to taking a stand on human rights issues. In fact, museums which are essentially a product of the post-Second World War universal human rights regime instigated by the United Nations in 1948.

Since any award is inevitably a subjective process, and the EMYA is no exception, the selection must be seen as a representative of the values that inform the decision of the jury.

Analysing the list of selected museums of influence (2021 edition) dealing with the difficult past, we can distinguish between war museums such as In Flanders Fields (Belgium), Tampere 1918 – Museum of the Finnish Civil War, and the War Childhood Museum in Sarajevo; museums of catastrophes like the Vasa Museum and the Mary Rose Museum (another sunken ship museum in Portsmouth, UK); museums of political history such as the German Emigration Centre in Bremerhaven and the European Solidarity Centre in Gdansk; cemeteries and museums reflecting upon the end of human relations like the Glasnevin Cemetery Museum in Dublin and the Museum of Broken Relationships in Zagreb; and finally, two memorial museums – The Žanis Lipke Memorial and the Mémorial ACTe (the Caribbean Centre of Expressions and Memory of the Slave trade and Slavery in the French Caribbean).

From a bird’s eye perspective, one cannot help noticing a pattern: practically all European remembrance topics are present.

According to Claus Leggewie’s Seven circles of European memory[9], these themes can be depicted graphically as ever-expanding circles, with the Holocaust as Europe’s negative founding myth at its core. This is followed by:

The second circle: The Gulag and Soviet communism;

The third circle: Expulsions and ethnic cleansing after war;

The fourth circle: Wars and crises as engines of European development;

The fifth circle: Colonial crimes;

The sixth circle: History of migration;

The seventh circle: European integration after 1945.

I am not suggesting that with this selection the EMF as a UK based charity would go against the political mainstream and pledge its allegiance to the European Union. What I am pointing out is the fact that the European collective memory landscape today isn’t complete without all these seven memory circles, with the majority of them being dark chapters of history. And these topics are indeed present in the selection because there is an influential museum or indeed a “museum of influence” for each of them.

What is striking is that the Žanis Lipke Memorial appears to be the only museum among the 50 dealing specifically with the Holocaust, even if not necessarily so termed by its founders.[10] The credit given by the most prestigious European museum award is just one side of the coin. The other is the responsibility that comes with it.

The question must be asked: is the Žanis Lipke Memorial living up to expectations of a ”museum of influence?” Or, in the words of Mr Hudson, does the Memorial help its visitors to become more self-confident?

The latter requires a clearly defined program and means to deliver it. Next, I will look at the historical background against which the unique formula of the Žanis Lipke Memorial and its interpretation and communication of the difficult past came about.

Living up to expectations

Professor Aivars Stranga was the co-editor of volume No 18 of the Commission of the Historians of Latvia published in 2006. In his introductory article ”Research and Memory of the Holocaust in Latvia,” he looks back 15 years of independent Holocaust research and developing memory culture in Latvia since 1991. The time of writing coincided with the end of the second term in office of the president of the republic Vaira Vīķe Freiberga, who during her eight years in office had encouraged voluminous research work on the Holocaust and other subjects of the recent history.

Stranga pointed out that the Commission of the Historians of Latvia was by far the largest historical research project in both periods of independent Latvia. In total, 27 volumes on 20th century history have been published. The project was ended in 2019 under the current president Egils Levits, who considers the mission accomplished.

According to Aiva Rozenberga, Vīķe-Freiberga’s long-time press secretary, the mission of the project was ”largely to confront Russia's attempts to use history to tarnish Latvia's image in the West as Moscow sought to slow Latvia’s accession to NATO and the EU by trying to portray Latvians as active participants in the Holocaust, and even as seeking to rehabilitate Nazism”[11].

Stranga concludes that the Holocaust now should become part of historical consciousness not so much through academic research, but primarily via popular books, movies, plays, monuments, and memorials, and in the many other ways that make up shared memory. He also hoped that plans for a monument to the rescuers of Jews at the former location of the Riga Choral Synagogue would come to fruition, and added:

It is right that memorials are visited; but they often stand lonely or get visits only occasionally – as a tribute to memory or even politics, and not as a cognitive or moral necessity.[12]

Another 15 years later, we can now assess three decades of independent interpretation and communication of the difficult past. So where do we stand in terms of shaping a popular shared memory of this historic subject?

Correct me if I’m wrong, but it appears that apart from the Commission of Historians which ran for 10 years and produced top class academic works, and the Monument to the Rescuers of Jews that was partially funded by President Vīķe-Freiberga and opened in 2007, there has been no other purposeful institutionalization of the memory of the Holocaust by the state.

The initiative, drive and imagination has to be sought elsewhere – in the private sector. The Žanis Lipke Memorial stands out as perhaps the most distinctive embodiment of the wish expressed by Stranga back in 2006 for the rescuer legacy to become part of our collective memory through a creative response. A response that was badly needed for the national interests in history politics in order to confront the Kremlins’ accusations, and its distortion of Latvia’s image in the West.

And again, it was President Vīķe-Freiberga who, responding to the invitation of the founders of the Žanis Lipke Memorial – Ārija Lipke, Māris Gailis and Augusts Sukuts, unveiled a memorial plaque at the house of the Žanis Lipke on the island of Ķīpsala in the early 2000s. It took a further decade for the idea of the memorial to materialize through donations from private individuals.

The Role of Creativity

As a ”museum of influence”, or at least one that is trying to live up to expectations, the Žanis Lipke Memorial has relied from the very start on cooperation with creative personalities in shaping its form and content.

What comes to your mind when you think of a memorial? Most likely it is the visual form, the architecture within the landscape where it is located. The signature building of the memorial by Latvian architect Zaiga Gaile not only got numerous awards locally and internationally[13] but since 2019 has also been listed as a state-protected cultural monument.[14] Together with the grand-scale Latvian National Library, it is one of only two 21st century public buildings listed to date in this country. Another milestone achievement.

But it goes beyond architecture. Even if you have been fortunate in finding of the right architect, you would need a whole creative team to get the hardware right – the scenographer, interior designer, decorative artist, composer of the ambient sound track etc. – who all contribute to the unique experience of space in three dimensions.

Once up and running, a proactive organisation also needs soft architecture, i.e. individuals who are either working full-time or on contracts. The world’s best museums have long known the value of the artist in residence, and the unexpected perspectives cooperation with artists can bring.

The Žanis Lipke Memorial has been fortunate in attracting a talented creative people to interpret the story it tells. After the opening in 2012 attended by the presidents of the State of Israel, Shimon Peres, and Latvia, Andris Bērziņš, the joint effort of the creative team was recognized by the Award for Excellence in Culture by the Ministry of Culture followed in 2014.[15]

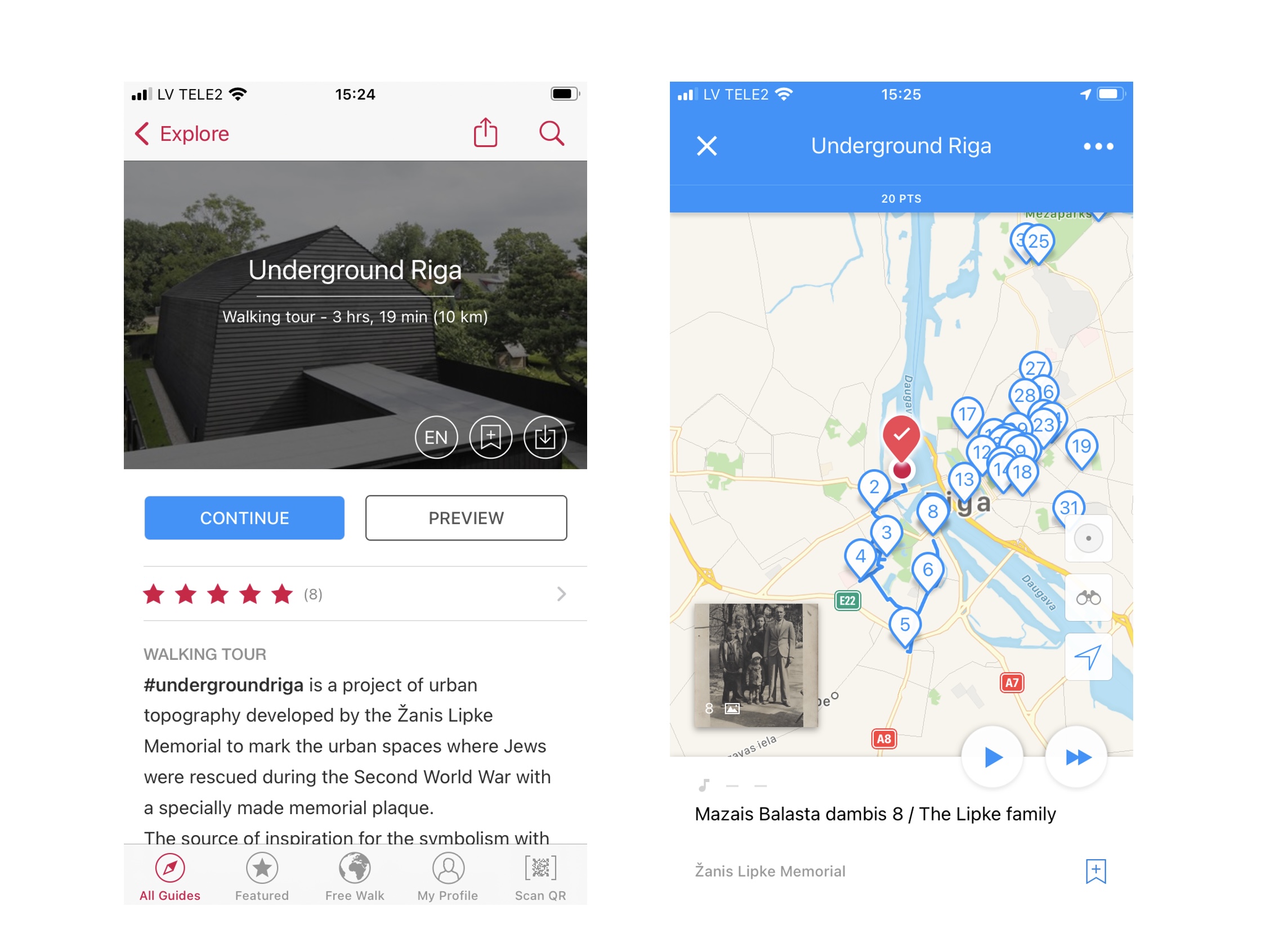

In 2014, the Memorial gained further recognition during Riga’s period as the European Capital of Culture. Municipal funding was available for furthering the museum’s work. This was achieved through the Underground Riga website, and memorial stones (Stolpersteine) were laid into the pavement on the sites of former hideouts. This gave a significant boost to the outreach work of the Memorial.

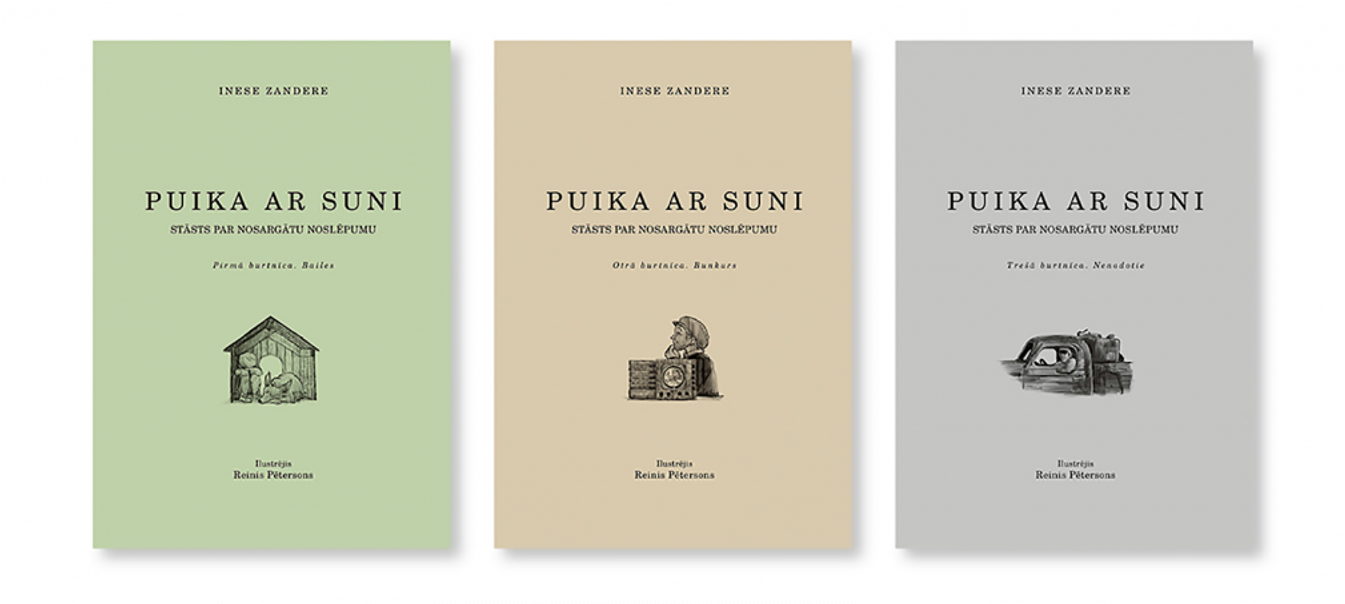

Probably the most important creative production of the Memorial thus far has been a children’s book commissioned from a well-known Latvian poet Inese Zandere. “Puika ar Suni” or A Boy with a Dog was first published in 2017.

This very popular book was initially planned as a trilogy, which it still might evolve into (the second part has already been published in Lithuanian). It was adapted as the full-length feature movie “Tēvs Nakts” (Father Night, retitled The Moverin English). Directed by Dāvis Sīmanis, it won in category Best Foreign Film at the 35th Haifa Film Festival.

In the fall of 2020, a theatrical adaptation of A Boy with a Dog was premiered at the Žanis Lipke Memorial by director Jānis Znotiņš and his children’s theatre company Istaba. The show has been now postponed until museum is open again to the public.

In addition to traditional means of communication such as exhibitions, publications and live exchange including lectures, discussions, and conferences, the Memorial is also experimenting with innovative digital forms of communication.

In April 2020, during the first wave of the corona pandemic, the aformentioned Underground Riga got an upgrade. Alongside a dozen new hideouts supplementing the digital map, a city walking audio guide app in Latvian, Russian, English and German was published on the iziTravel platform.

The response was positive, particularly from locals who couldn’t travel abroad and used this opportunity to walk the streets of Riga while listening to the story.

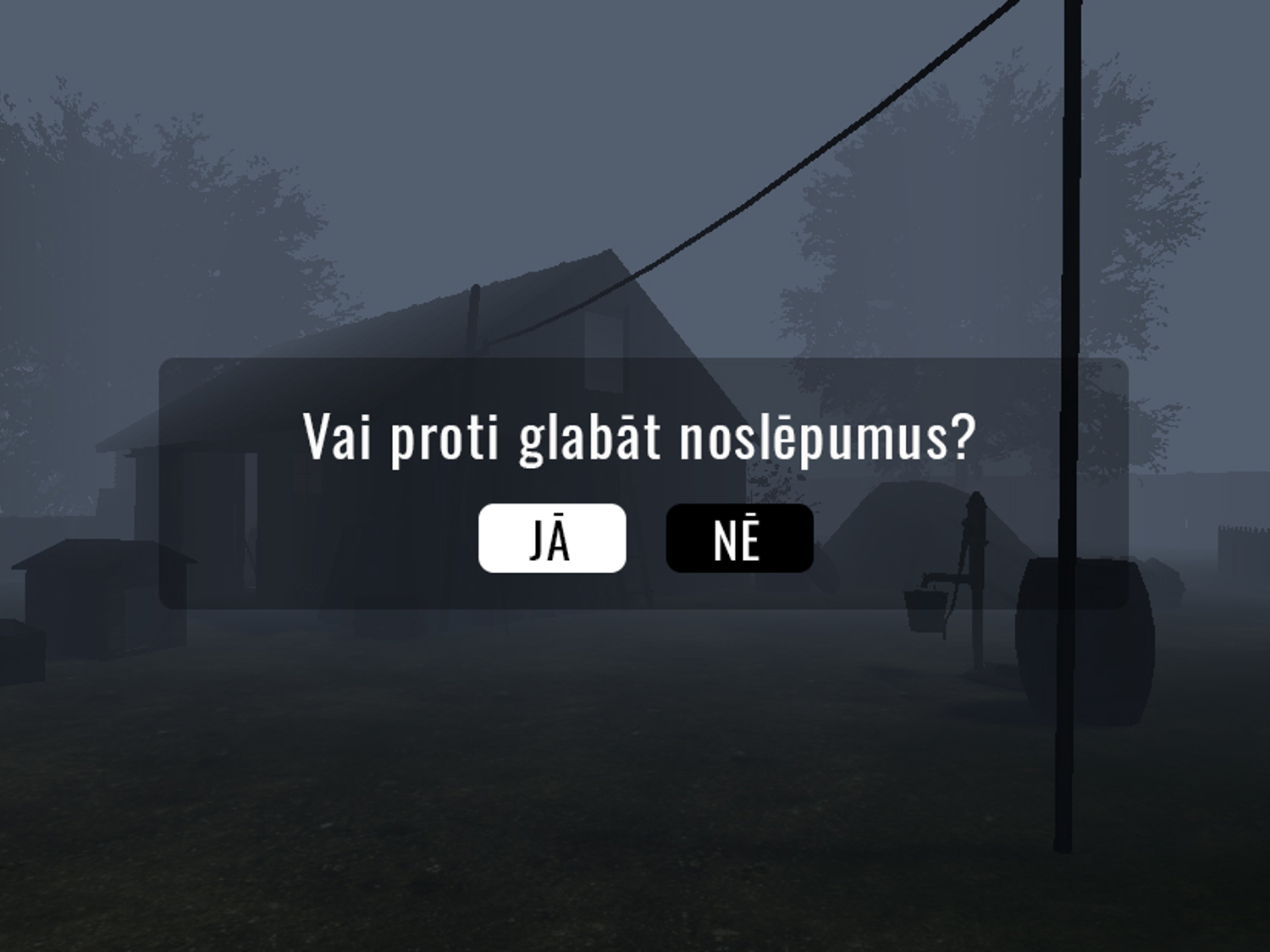

Another recent product is the Virtual Reality Lipke Bunker, the first of its kind in Latvian museums. First presented last November at the symposium dedicated to the 120th anniversary of Žanis Liple, the VR is now ready for museum visitors and will be published on the Oculus Facebook platform. The Lipke bunker VR was inspired by the Secret Annex VR of the Anne Frank House.

A New Vision

The museum’s tenth anniversary in 2012 marked the beginning of a new vision for the development of the organisation. The process of influential communication of the difficult past by putting more effort into educational work is at the heart of this vision. Its working title is A House of Courage[16], the new educational centre of the Žanis Lipke Memorial.

The 120th anniversary of Žanis Lipke last year was spent rising funds and debating in various formats about what the House of Courage should be. Architects, urban planners, educators, historians, and other experts participated in discussions, talks, and the closing conference in cooperation with University of Latvia MemoTours project. It was entitled Civic courage for a democratic future – Žanis Lipke 120.

The Anne Frank House, our role model in educational work, as a business model and in terms of the quality of products and services, demonstrates that a memorial museum dealing with the difficult past shouldn’t limit itself thematically not chronologically to the bygone dramatic events. While maintaining its core mission of safeguarding the memory of the person and the family concerned, it can also be a truly contemporary history museum and a civic education centre, with a programme that especially young people can relate to.

So much for the justification, if one was needed, of why the Memorial began a fundraising campaign to secure the available plot of land next to the historic site. By teaming up with creative professionals and the Uniting History foundation, who doubled each donated euro, the target of 350k euros was reached. The raised extra sum will suffice to clear the plot of land and pay for the construction project.

Meanwhile, by Christmas 2020, with the help of the State Cultural Capital Foundation, the architectural completion of the House of Courage had attracted 15 projects. The award-winning proposal[17] was submitted by MADE architects, whose portfolio includes innovative school projects.

Given that the story of Žanis Lipke is already included in the school curriculum, we believe the House of Courage can become a partner for teachers in the learning process.

However, these new developments entail uncertainty regarding the role given by the government to NGOs like ours in the formal education process, which would make long-term planning possible for a small organization.

For now, the annual operating budget of the Memorial is covered by an annually requested and approved grant in aid from the Ministry of Culture, which allows free entry for now. However, a recent study on the memorial’s socioeconomic impact[18] shows that despite it clearly being underfunded, it delivers far beyond any other cultural venue of its size.

Adding a new wing to the Memorial world mean changing the business model in view of the growing number of tasks. To make the educational centre work, extra funding and staff will be needed. The question is whether the educational services provided by the Memorial will be required by the state and/or municipality which proved to be the major funding source thus far.

For example, in line with the new national civic and patriotic education plan, a special National Defence Training scheme is gradually being introduced to all Latvian schools. By 2024, National Defence Training will become mandatory in the general school curriculum. It will be administered by the Latvian Cadet Force under the Ministry of Defence, who will train and accredit the instructors.

Becoming part of the National Defence Training ecosystem may be one of the ways forward for the House of Courage. Or perhaps an NGO active in the field of civic education needs to take a different, more autonomous direction?

The experience of world-renowned leaders in civic education such as the Anne Frank House shows that the bottom-up approach in developing civic education programming at memorial museums can take decades to become mainstream. It is also unlikely that the House of Courage will be financially fully independent. Such a business model simply doesn’t exist in this region. However, the planning of the programming of the new educational centre foresee a number of ways of revenue generation including a museum shop and a café, and premises rental. Additionally, the staff and consultants of Memorial are exploring the ways how the planned maker space could work to promote creativity and simultaneously be monetized.

Conclusion

In Conclusion, while the answers to these larger sustainability questions are pending, there are practical tasks to be completed in 2021.

Preparations are underway on a blueprint for the House of Courage. The winning architectural team MADE architects is developing the construction plan for the new building, which will feature both traditional and innovative learning environments, including classrooms and an auditorium, a multimedia space, a makerspace, and a quite meditation room to the original size of Lipke’s bunker.

The museum team is taking part a training program on the role of memory culture in civic education in order to elaborate guidelines for methodology of civic education in the planned education centre. The training program is funded by the German Embassy in Latvia and will take place in May 2021, coinciding with the International Museum Day. A larger public events programme around the training and developing a learning content for the House of Courage is planned for the autumn 2021.

Both lines of work, i.e. on the form and content, will be ammalgamated into a blueprint for the House of Courage by 2022, followed eventually by construction work.

It remains to be seen if the formula “built by private money, funded from the public purse” will work this time round. Both parties will need to strike a new deal. Preferably if the construction is at least partially funded from the public money so as to increase the public stakeholder’s interest in the new educational centre which has a single purpose – to serve the public at large.

If there is one cultural institution in Latvia which has proved the efficacy of Public-Private-Partnership over the last decade, it is the Žanis Lipke Memorial. It can therefore have a larger impact on the interpretation and communication of difficult past serving national interests through its civic education programming. Provided that the state, the municipality, and the private sector keep working together.

This paper was presented on 26.02.2021 at the 79th International Scientific Conference of the University of Latvia section "Difficult Heritage: Communication and Interpretation". The conference was organized by the MemoTours “Difficult Heritage: Between Memorisation and Contemporary Tourism Production and Consumption. The Case of Holocaust Sites In Latvia (abbreviation – MemoTours)” – a research project of the University of Latvia Philosophy and Sociology Institute.

Images from Žanis Lipke Memorial Archive

[1] Hudson, K. (1987). Museums of Influence. Cambridge. Cambridge University Press.

[2] O’Neill, M., Sandhal, J., Mouliou, M. (Eds.). (2021). Revisiting Museums of Influence. Four Decades of Innovation and Public Quality in European Museums. Abingdon. Routledge.

[3] Website of European Museum Formum. Accessible from: https://europeanforum.museum/ [08.02.2021].

[4] Website of the thinktank Creative Museum. Available from: http://www.creativemuseum.lv/lv/raksti/dienasgramata/30-neatkarigas-muzejniecibas-gadi-creative-museum-saruna-ar-scenografu-zana-lipkes-memoriala-scenarija-autoru-viktoru-jansonu-ii-dala [08.02.2021].

[5] Gnedovsky, M. (2021). Žanis Lipke Memorial in O’Neill, M., Sandhal, J., Mouliou, M. (Eds.). (2021). ‘Revisiting Museums of Influence. Four Decades of Innovation and Public Quality in European Museums’. Abingdon. Routledge, 157-159.

[6] Shandler, J. (2018). Anne, from Diarist to Icon in ‘Anne Frank House’. Anne Frank Stichting. Amsterdam.

[7] Website of the Vasa Museum. Available from: https://www.vasamuseet.se/en/about-the-vasa-museum [18.02.2021].

[8] Lennon, J., Foley, M. (2000). Dark Tourism: The Attraction of Death and Disaster. London, Continuum.

[9] Leggewie, C. (2010) Seven circles of European memory. Available from: https://www.eurozine.com/seven-circles-of-european-memory/ [18.02.2021].

[10] Youtube channel of Creative Museum. Muzeji un radošās industrijas: Māris Gailis. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJf7izQNH3k [03.03.2021].

[11] Website of Latvijas Avīze. Available from: https://www.la.lv/vesturnieku-komisijas-vieta-mobila-sadarbiba [21.02.2021].

[12] Website of the President of the Republic of Latvia. Available from: https://www.president.lv/storage/kcfinder/files/item_1641_Vesturnieku_komisijas_raksti_18_sejums.pdf [21.02.2021].

[13] Latvian Architecture Award for 2012; Arhitext Design Foundation’s Award at the East Centric Architecture Triennale in October 2013.

[14] Website of Public broadcasting of Latvia (LSM.LV). Žaņa Lipkes memoriāls iekļauts Valsts aizsargājamo kultūras pieminekļu sarakstā. Available from: https://www.lsm.lv/raksts/kultura/kulturtelpa/zana-lipkes-memorials-ieklauts-valsts-aizsargajamo-kulturas-piemineklu-saraksta.a317911/ [03.03.2021].

[15] Website of the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Latvia. Available from: https://www.km.gov.lv/sites/km/files/data_content/ibk.20laureati2020141.pdf [21.02.2021].

[16] Website of the Žanis Lipke Memorial. House of Courage. Available from: https://lipke.lv/en/house-of-courage/[03.03.2021].

[17] Website of the Žanis Lipke Memorial. Ideju konkurss. Available from: https://lipke.lv/drosmes-maja/#content-item-5[03.03.2021].

[18] Neija, A. (2020) Muzeja “Žaņa Lipkes memoriāls” sociāli ekonomiskās ietekmes izvērtējums. In preparation.